Steve Bruns, MPP, Staff Writer, Brief Policy Perspectives

Just this past summer, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Health Plan announced that insurance premiums in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace would rise by eight percent, on average, in 2018 to compensate for the anticipated increase in health care costs. Fast forward to mid-October, when UPMC announced a more dramatic increase: premiums would be 41 percent higher, on average, in 2018.

What happened between then and now?

On October 12, President Trump signed an executive order to expand the availability of cheaper, skimpier health plans, and later that same day the White House announced its refusal to pay cost-sharing subsidies to insurers in the ACA marketplace. The wonky details aside, these two policy actions are oriented toward a singular political goal: to fulfill a campaign promise to upend the ACA, President Obama’s signature legislative achievement. But pursuing this goal is likely to come at a great cost to many Americans, including vulnerable Americans who need insurance coverage the most (the sick and the elderly), young and healthy Americans who opt for cheaper yet less reliable insurance coverage, and ultimately, the general American taxpayer.

If implemented as written, the President’s executive order would benefit the young and healthy at the expense of the sick and elderly. While the executive order does not have the force of law, it does instruct the Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, and Treasury to write new regulations easing the federal rules governing association health plans and short-term insurance plans. Once finalized, the regulations would likely expand the availability of cheaper plans with less coverage benefits. This is because it would exempt association health plans and short-term insurance plans from meeting the ACA’s essential health benefits requirement—mandating that insurers cover benefits ranging from hospital care to prescription drugs to maternity care—as well as the requirement that insurance cover a minimal percentage of a person’s medical bills.

Such plans would likely lure younger and healthier beneficiaries away from the more expensive plans offered in the ACA marketplace, and therefore drive up premiums for the older, sicker groups who remain in the ACA market because they need more comprehensive coverage. However, even those who seemingly benefit from a cheaper association health plan would do so at their own risk; often referred to as “junk” plans, association health plans are traditionally rife with fraud and sometimes fail to pay beneficiaries’ medical bills due to insolvency.

Although the executive order at least portends to benefit the young and healthy, the administration’s refusal to pay cost-sharing reduction (CSR) subsidies amounts to a loss for nearly every key stakeholder in the ACA insurance marketplace. The ACA mandated that the federal government pay CSR subsidies to compensate insurers for lowering the out-of-pocket costs, deductibles, and copayments for low-income people who earn too much to be eligible for Medicaid. Without CSR payments, the law still requires that insurers reduce costs for lower-income people. Insurers will either raise premiums to make up for lost revenue or flee the marketplace. If insurance companies do raise premiums, the federal government, per the law, is on the hook for much of those costs. Thus, the decision to stop the payments has no clear winners, with wide-ranging negative consequences for the government, the insured, and the insurers. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities:

- ACA premiums will rise by an additional 20% in 2018.

- The federal government will add $194 billion to the national debt over the next decade.

- The number of uninsured will rise by one million in 2018.

- Insurance companies who already set premiums on the assumption that the payments would continue in 2018 will lose revenue.

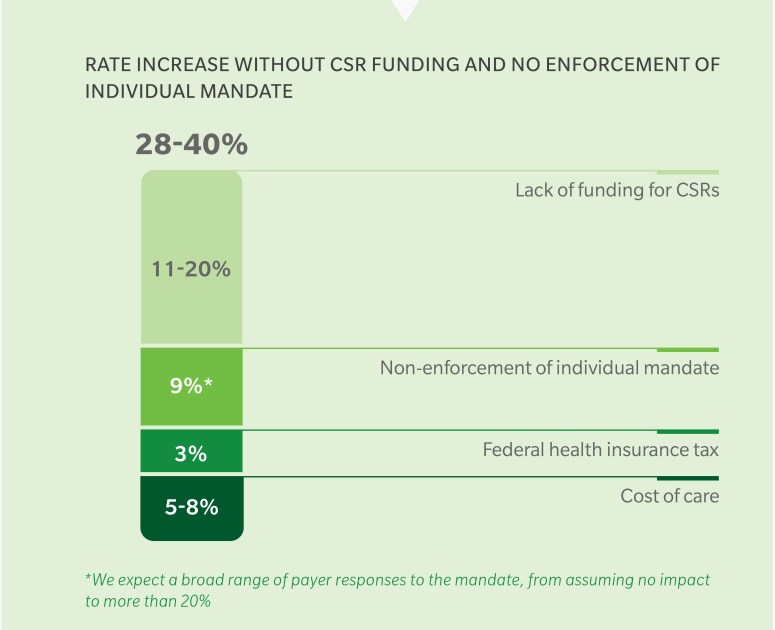

The administration’s decision to not pay CSR subsidies is not set in stone, however, as Congress can still appropriate funding for the subsidies despite the White House’s lack of support. No matter how Congress acts to potentially support the current health law, the White House has already taken a series of actions over the last several months aimed at destabilizing the marketplace: it halved the ACA open enrollment period from 90 days to 45 days, cut the ACA advertising budget by 90 percent, reduced funding for in-person outreach by 40 percent, and has hinted that it might stop enforcement of the individual mandate. Taken together, these policy decisions have substantially added to premium increases in 2018 (Figure 1).

Certainly the ACA is not perfect, but it is a law that can and ought to be reformed rather than subverted or repealed outright. The ACA produced historic gains in insurance coverage for at least 13 million Americans, bringing the uninsured rate to a historic low, and it implemented payment and billing reforms intended to reduce the cost and improve the quality of health care. Considering the ACA’s 51 percent approval rating, it seems that the White House’s efforts to undermine the ACA are not just bad policy, but may be bad politics too.