Jerry Wei, MPP

A proliferation of data has increasingly come to define the modern condition. We now use data to track fitness (Fitbit), hail cabs (Uber), and stalk love interests (Google). With technological advances, data are also being used as metrics to assess organizational and personnel performance.

In theory, metrics—standardized, measurable, and objective—should work as measures of success or progress. As a result, accountability culture in business, nonprofits, and government has never been more popular. An entire industry has grown up around the assembly and analysis of “metrics,” “indicators,” and “performance measures.”

Is this a good thing? Not for historian Jerry Muller. In an essay for The American Interest, he argues that “…the virtues of accountability metrics have been oversold and their costs are under-appreciated.” Three core pitfalls of what he deems “Metric Madness” emerge from his argument:

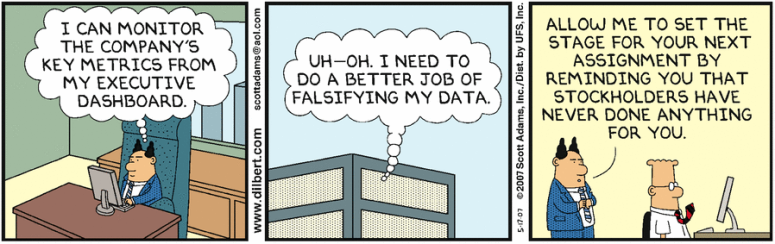

(1) Metrics can be gamed. Accountability metrics are high-stakes. Funding or employment is often contingent on performance metrics, and the accountable are often evaluated against just a few metrics. This generates an environment ripe for gaming and cheating.

K-12 education is emblematic of this problem. Federal and state education programs have sought to use testing to assess educational attainment, tying funding and teachers’ jobs to the results. In response, educators do not simply “teach better.” Instead, school districts reclassify poor performers out of the testing pool. Teachers divert time away from teaching their subjects to test prep. Others alter students’ answers.

This problem is not just limited to government. Corporate boards have tied CEO pay and tenure to quarterly earnings reports. This has led CEOs to pursue short-run profits at the expense of long-run investments and strategies. In medicine, success rates are publicly documented on “surgical report cards,” leading heart surgeons to turn away sicker patients to up their stats.

(2) Intangibles are neglected. By using metrics, decision-makers substitute experience and judgment, which may have elevated less measurable activities, for the precision of statistics. As a result, those held accountable focus on measurable activities at the expense of the larger picture.

Police departments rely heavily on metrics to hold officers accountable to the public. Systems like CompStat link officer performance directly to arrest and crime data in their districts. Muller points to the Baltimore Police Department, where performance metrics treat the arrests of petty drug sellers and top drug lords equally. Since the metric made no distinction for importance, detectives focused on the quick and easy arrests instead of time-consuming investigations of drug kingpins.

The easily measurable also wins out in R&D programs. More and more, companies use analytical tools as the sole arbiter of funding, eliminating professional judgment. As a result, “short-term projects with more predictable outcomes beat out the long-term investments,” which spur innovation.

(3) Metrics are measurable, not accurate. The two pitfalls above emerge out of this third, fundamental issue. As Muller states:

“…the attempt to measure performance, however difficult it can be, is intrinsically desirable if what is actually measured is a reasonable proxy for what is intended to be measured. But that is not always the case, and between the two is where the blind spots form.”

Is it right to hold people accountable for a metric that doesn’t capture what it intended? What is the value to business leaders and policymakers of a flawed metric?

It’s not just that metrics may be inaccurate – they are also are expensive. Countless person-hours are spent compiling, sharing, analyzing, and understanding metrics.

Metric Madness has led to low morale, loss of initiative, and yes, gaming, cheating, and neglect. For an honest decision-maker, this should be a problem.

What now?

It’s easy to get cynical. Many organizations simply “feed the beast,” knowing that other considerations trump the metrics when determining accountability.

Take the State Department’s “Agency Priority Goals,” which are publicly reported on Performance.gov. Does anyone think that “Climate Change,” “Food Security,” and “Excellence in Consular Delivery” are the three most important goals for the State Department? Or that anyone is seriously using these goals to make funding and planning decisions?

Muller doesn’t offer much in the way of solutions. He suggests that accountability metrics are less effective when imposed from above by those detached organizationally from the activity being measured. He also argues that, given the costs, decisions-makers should simply consider not assembling metrics when the gains are few.

However, we can do more. Policy and business leaders should reach out to broader constituencies when developing metrics, particularly those whom the metrics will hold accountable. These are the people with experience, who understand the nuances of the business or policy issue the metric is trying to quantify.

For advocates and activists, higher education may be a good model. Universities have successfully fought off President Obama’s ill-advised college rating scheme, which would have tied federal funds to measures of “access, affordability, and outcomes.” Despite this defeat, the Department of Education is promising to collect “more data than ever before”– revealing how policymakers confound data collection with fostering accountability.

Some lessons for advocates and activists are:

- Take action at the policy formation phase, not during execution or evaluation.

- Work collaboratively with decision-makers when possible.

- Focus on the un-sexy task of analyzing proposed metrics and organizing against them when needed.

- Engage the public by connecting these metrics to real-world impacts when translating these initiatives to the public.

Following these steps does not guarantee that government and other organizations will be brought back to their senses, but it’s a step forward. Countering Metric Madness will take sustained energy, care, and attention.

3 thoughts on “A Good Metric is Hard to Find”